Good Wood, In Bad Books.

Why Uncle Nearest's challenges shine a light on bad business practice and NZ distilleries can't afford to simply knock on wood.

From Monday 23 February, This Tastes Good returns with two rising stars and some Incrediballs. But for now, scandal unfolds in the barrelhouse of brand darling and whisky juggernaut Uncle Nearest.

Valuable lessons for anyone looking at (or cooking) the books.

I was visiting Nearest Green Distillery, the Tennessee home of Uncle Nearest’s Premium Whiskey in May 2024, fourteen months before the big legal envelopes started arriving at their door. Big, beautiful copper stills glinted through the stillhouse windows under the blazing sun. No visit inside though, according to the guide. No point, they were still not wired in after being installed years prior. Not unplugged, not being serviced. Never once fired up, not even as an expensive tourist attraction at the place they call Malt Disney World. If you know the price of copper these days, you’ll understand how extraordinary a concept it is to spend that much money and then never bother turning them on. After all, if you’re in the whisky business, making whisky is usually pretty key to making money.

The brand-tastic whisky I’d been following since 2018 wasn’t being made there either, as it turned out. Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey was actually distilling (by their team, I was assured) down the road at a contracted facility while the brand equity compounded at an extraordinary rate. Beautiful facilities. Great story. Growing faster than almost any whisky brand in American history. And those stills, sitting cold and quiet in the Tennessee heat.

The more questions I asked, the more my guide’s frustration showed.

It was about then I knew something was very, very wrong in Shelbyville, TN.

The Uncle Nearest Problem

If you haven’t been following the legal drama unfolding around Uncle Nearest, here’s what you need to know. Founded in 2017 by Fawn and Keith Weaver to honour Nathan “Nearest” Green — the man historically credited with teaching Jack Daniel his craft, and America’s first known Black master distiller — it became the fastest-growing American whiskey brand in history. By 2024, it was supposedly stocked in more than 30,000 venues across 12 countries. Fawn Weaver claimed a valuation of $1 billion and had raised capital from over 160 individual investors at an average of around $500,000 each. It was the kind of brand story that makes the industry feel important.

Then the numbers arrived.

In July 2025, primary lender Farm Credit Mid-America filed suit in a federal Tennessee court, alleging Uncle Nearest had defaulted on more than $108 million in loans. Among the sharpest accusations: the company had overstated its barrel inventory by $21 million, inflating its borrowing base to access larger credit draws. When third-party inspectors conducted a physical collateral check, significant discrepancies emerged between the barrels that existed on paper and those that existed in the warehouse. The lawsuit also alleges that the borrowers bought an estate on Martha's Vineyard for $2 million and sold futures on their business at a discounted cost.

It is undisputed that a then-officer of the company misrepresented Uncle Nearest’s barrel inventory to obtain an additional $24 million under the revolving loan. The Weavers maintain they were unaware, placing responsibility on former CFO Michael Senzaki, who was fired in 2024. Senzaki denies wrongdoing. A federal judge ordered the company into receivership in August 2025. The court-appointed receiver found that company records before 2024 had been deleted, that Uncle Nearest owed an additional $50 million to vendors and creditors beyond the original loan, and that federal tax returns had not been filed since 2018.

The question of fraud versus catastrophic mismanagement is ultimately for the courts to resolve. But the structural problem at the heart of the case — barrels used as collateral at valuations that didn’t survive scrutiny — isn’t unique to Uncle Nearest. It’s a feature of the craft spirits investment model globally.

Promises, Knocks on Wood and Big Dreams

Anyone willing to spend an afternoon on PledgeMe or Snowball Effect can read what New Zealand distilleries have told retail investors about what their barrels are worth, what they’ll sell for, and approximately when. That’s the value of a public document, much the same as the Companies Register, the Security Register and the Insolvency Register.

So let’s take a look at two campaigns, as illustrations of an industry-wide challenge: in a market still writing its own rules. With no established secondary market for NZ aged whisky casks and no historical price benchmarks at auction, optimistic projection isn’t a character flaw. It’s almost structurally required to make a compelling case for investment. The tension is that the market you’re projecting into eight years from now may not resemble the one you’re standing in today, as recently proven by a global spirits over-supply. Which shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone investing in agricultural commodities.

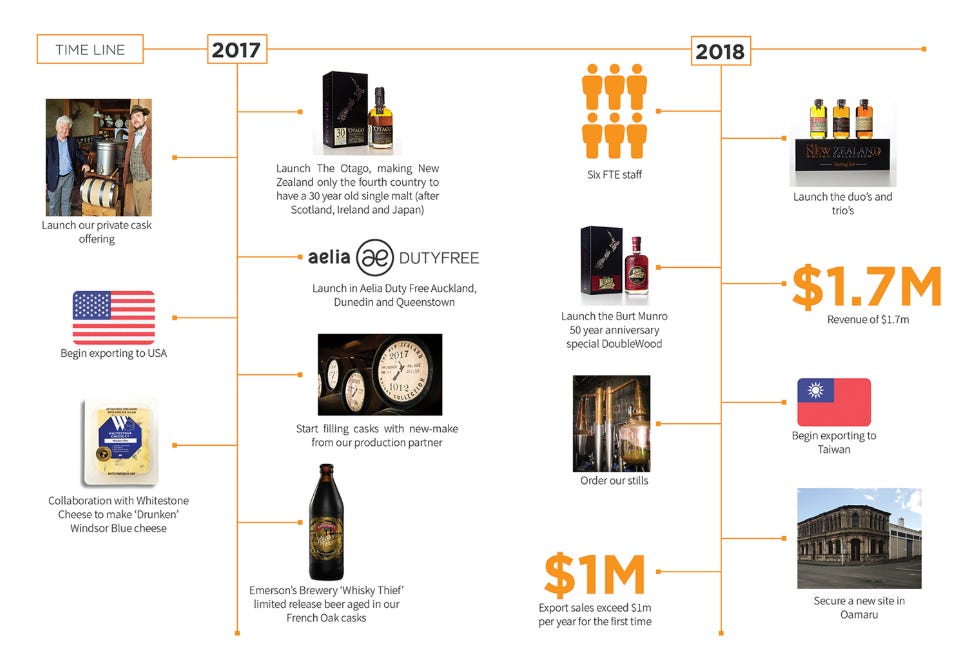

In late 2018, The NZ Whisky Collection raised $780,030 via PledgeMe to fit out a distillery in Oamaru and expand cask production. The offer was pitched against a booming global appetite for new world whisky — Japanese, Taiwanese, Australian, now New Zealand. The language was confident about trajectory: traditional brands declining, craft experiences ascendant. All reasonable to say in 2018.

What’s harder to evaluate now is where those projections sit against a retail whisky market that has since become significantly more crowded and price-sensitive. They got the stills and eventually installed them in Dunedin.

More recently, Reefton Distilling Co. raised $1.7 million via Snowball Effect in 2024 to scale whisky inventory and warehousing. Reefton is a serious operation with genuine credentials—Little Biddy Gin has driven successful revenue. Their raise positioned maturing cask inventory as a core asset in the company’s value story. Which it is.

Cardrona Distillery took on private equity to cashflow operations before selling to International Beverage, Scapegrace have a group of investors. Investment tends to be an easier answer than traditional bank business lending in NZ, due to the nature and risk associated with the industry.

The question that applies to every whisky business raising on the promise of aged inventory is the same one: is the projected value of that inventory grounded in market reality, and could a lender verify it if they needed to? Inventory is only an asset if you can actually sell it when required. Otherwise we might call them liabilities.

The type of projections you produce tells you a lot about the strength and validity of the business model.

Across the Tasman, It Already Got Serious and Scandalous

Between cautiously optimistic market projections and genuine ambition, every aged spirit valuation assumes someone will inevitably pay more for what time and wood have produced. But what happens when the barrels are filled with nothing but air?

New Zealand has no documented cases of barrel investment fraud, and nothing in the crowdfunding campaigns examined here suggests anything other than genuine attempts to build whisky businesses. But across the Tasman, the worst-case version of this story is still playing out in a Hobart courtroom.

Keith Batt, founder of Nant Distilling, appeared before the Hobart Magistrates’ Court in January 2025, charged with 736 alleged offences — including 622 counts of fraud — relating to a barrel investment scheme that allegedly ran from 2007 to 2016. The scheme offered investors two barrels of Tasmanian single malt for AU$25,000, with a guaranteed 9.55% return at maturation. One investor paid approximately $170,000 for 14 barrels. He was later told his barrels did not exist.

When Australian Whisky Holdings undertook a forensic audit prior to purchasing the distillery, they found over 1,300 barrels that simply didn’t exist — 720 missing, others never filled, others already decanted and sold without investors’ knowledge. Some barrels had been filled well below the industry standard ABV, meaning the spirit would eventually fall below the legal threshold to be classified as whisky at all. The owner names and barrel numbers had been sanded off others.

This is the extreme end. But industry observers watching the broader Australian craft whisky market have noted structural vulnerabilities that predate Nant and don’t require bad intent to cause harm. Several small distilleries have closed, stopped production, or quietly dumped maturing stock to claw back funds — because the business model couldn’t sustain the long wait for aged inventory to generate revenue. The gap between when you fill a barrel and when you can sell what’s in it is the central financial challenge of every whisky business. Creative accounting, or optimistic projection, can paper over it for only so long. And given the whisky industry is largely ungoverned here in Australasia, the question of who is paying attention to whether the casks on the balance sheet match the casks in the barrel hall is one worth sitting with.

Scandal gets headlines. Bad business practice is often ignored.

Every Dollar in a Barrel Is a Bet

There is financial reality that whisky-making romance tends to obscure: capital expenditure can’t be wishful thinking. Every dollar you spend building a distillery, purchasing casks, filling barrels, and paying rent on bonded storage has to generate a return. Especially when it’s not your money to begin with. The clock starts running the moment new make spirit goes into wood — not when it comes out. Your exposure as a business is how long you can hold stock or cover the cost of time, which is why so many distilleries are now throttling production back.

That makes aged whisky inventory a uniquely punishing asset class. It’s not just illiquid; it’s actively expensive to hold. You’re paying the cost of capital — the interest on a loan, or the opportunity cost of equity tied up — on an asset that won’t generate revenue for years. Whether you’re running your business on debt or on equity raised with optimistic projections, you’re still running it on a future position. Long-horizon inventory doesn’t compress to fit a short-horizon cashflow problem.

The wine industry is providing an object lesson in what happens when the market moves against you before the asset matures. In California, the scale of recent closures is staggering: Vintage Wine Estates — which owned more than 60 brands and went public at a $600 million valuation in 2021 — filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2024, weighed down by $310 million in debt after overextending through acquisitions. Gallo, the world’s largest wine producer by volume, closed multiple facilities across Napa and Sonoma through 2024 and into 2025, shedding capacity it built for a market that no longer exists at that scale. The 2024 California wine grape crush hit a 20-year low. Growers are replacing vines with alternative cash crops.

Australia is no different. Treasury Wine Estates closed its Karadoc winery in Victoria, describing it as a “last resort.” Accolade Wines — Hardy’s, Croser, Banrock Station — ended up in the hands of distressed asset specialists after private equity reached end of tolerance. In the Riverland and Barossa, some growers are walking away from vineyards without seeking a buyer, because the cost of administration and asset disposal exceeds what a distressed sale would recover. This is the end stage of a business model that borrowed against future market conditions that didn’t arrive.

Whisky isn’t wine, and the production cycle differences matter. Similarly with craft beer that is also wrestling with new ways of funding business as usual, not even growth. But the underlying equation is identical: if the gap between what you spend now and what you receive later is funded by debt or investor optimism rather than genuine market data, you are exposed.

What the Lender Sees

Aged spirits inventory valued on a projected future sale price is fundamentally different from inventory valued at cost. The gap between those two numbers is where risk lives — specifically, the unknown cost of converting cost-basis inventory into that projected value, in a market nobody can fully predict.

In New Zealand, where there’s no established secondary market for domestic whisky casks and no historical price data for what a mature NZ single malt actually fetches, those projections are aspirational almost by necessity. For a business with genuine quality and patient investors, that’s a manageable position. For one facing a cash crunch before the barrels are ready, the gap closes very fast.

Any NZ distillery that has raised public capital on the promise of maturing stock owes its investors clear answers to a few basic questions: What’s the cost-basis valuation of current inventory? What are the projected depletion timelines, and are they on track? What’s the plan if the aged whisky takes longer, or fetches less, than originally modelled?

The Books Don’t Lie. Sometimes Owners Do.

The Uncle Nearest evidence keeps circling closer and closer to this inevitable truth bomb: business failure at this scale doesn’t arrive suddenly. It’s constructed, slowly, through a series of decisions that each felt defensible at the time. Another draw on the loan. Creating new entities to borrow and spread risk, moving money and assets to cashflow payroll. Another quarter where the depletion numbers weren’t quite what the model predicted, but the brand was growing so the trajectory was fine.

Founders in the craft spirits sector are almost always product people first. That’s not a criticism but it also means that the gap between what a founder understands about maturation, flavour development, and cask selection, and what they understand about their own balance sheet, can be large. The best ones identify the gaps, learn fast and surround themselves with experience and experts. The job of the Boss, whether CEO or Founder, is to know, to steer and to deliver good business, regardless of what the business is.

Fawn Weaver has maintained throughout the Uncle Nearest proceedings that she was unaware of the inflated barrel inventory figures. That may be entirely true. But “I didn’t know” is a statement about information flow, not a defence of governance. When you sign the loan documents, when your name is on the entity, when investors have written cheques on the basis of projections you presented — the books are your responsibility. Not your CFO’s. Not your accountant’s. Yours. Delegating crunching numbers is reasonable. Abdicating responsibility for them is not.

This matters for New Zealand’s craft distillery sector because the conditions that enabled the Uncle Nearest situation — operating debt as a growth strategy, barrel valuations that outpace reality, retail investors whose enthusiasm exceeds their financial analysis, lack of validated business model and governance — are not unique to Tennessee. The question isn’t whether NZ distillers are honest. The question is whether our businesses are literate: in best business practice, business finance and projections and building a profitable model.

Liquidation and going out of business are not things that happen to you. They are, with rare exceptions, the compounded result of decisions: to grow faster than cashflow supports, to value assets at what you need them to be worth rather than what they are, over-estimation of market opportunity, cost of customer acquisition and market repositioning. Every one of those decisions is a choice. They rarely feel like choices at the time. They feel like strategy, or necessity, or just keeping the lights on one more quarter. But they accumulate, and the bill arrives, and by then the options have narrowed considerably.

Even if a miracle investor came along to soak up Uncle Nearest’s $108m Farm Credit loan, the receiver estimates you’d need a purchase price of $250m just to tidy up the remaining debt ledger before you could turn the lights back on, not accounting for what it costs to turn the lights on at a $50m distillery. (Ask the Scapegrace boys at Lake Dunstan).

The distilleries that survive are the ones run by leaders who are willing to be honest with themselves about the numbers and learn what it takes to run a business by the books, instead of trying to magic up results that fit a farcical projection. It can be learned. It has to be.

Perhaps best summed up as yes, you have to spend money to make money. But you better show us exactly how the money you spend will generate the revenue at a price worth the cost.

Managing the Forecast When You Can’t Control the Market

The distilleries most likely to navigate this environment successfully share one characteristic: they treat their financial projections as living documents rather than sales documents. And they don’t take on debt that can’t be financed out of real cashflow. These are not sophisticated disciplines. They are the minimum viable requirement for running a business that holds long-horizon assets in a variable market. The fact that so many operators in this sector treat them as optional extras is precisely why the sector produces so many cautionary tales.

The first question I always ask a spirits brand is not about sales figures. It’s about depletions. Sales figures tell you what left your warehouse. Depletions tell you what actually sold off the shelf. The gap between those two numbers is inventory sitting in a distributor’s warehouse or retailer’s shelf, which is not the same thing as measurable consumer demand. Brands that track and communicate depletion metrics honestly have a real-time read on actual product movement. Brands that report only sales figures, or conflate the two, are either deceiving their investors or deceiving themselves. Sell-through is the realest validator of whether a market exists for your product at your price point, and it’s the metric every investor in a craft spirits business should be asking for first.

The second discipline is scenario planning against that data — not one optimistic trajectory, but a range. What does the business look like if sell-through tracks 20% below projection for the first two years of release? What if the premium whisky category softens by the time your aged stock is ready? What levers exist to generate cashflow in the meantime — contract distilling for other producers, early release of younger expressions, cellar door revenue? The distilleries with answers to these questions before they’re needed are the ones that survive the market moving sideways. Every business model needs a net-zero option: a clear, honest picture of exactly how to keep the lights on without profit, and for how long.

The third discipline follows: value inventory conservatively, and generate revenue aggressively. Cost-basis valuation — what it actually cost to produce and store the spirit — is defensible to a lender, an auditor, and an investor. Projected future market value is a forecast, and it should be labelled as one. The gap between those two numbers is your exposure. Your best business solutions start with what the numbers actually tell you, and what you can do with the resources you have.

Most of what Uncle Nearest is experiencing is a case of bad business leadership, not bad whisky or a bad market. Those circumstances only compound the problem. Brand equity and founder charisma carried it far further than the balance sheet could justify — which is exactly the warning, not the comfort.

The New Zealand spirits industry is genuinely exciting. It deserves business leaders who are as rigorous about their books as they are passionate about their product. Those two things are not in tension. One is what makes the other sustainable.

The barrel will cost you money every single day it sits in that warehouse, regardless of how good the story is. The question is whether you know exactly how much, exactly why, and exactly what you’re going to do about it. The Uncle Nearest story should be the wake-up call to every NZ spirits business owner to get their head in the books, get sharper than ever on realistic market predictions and sharpen the knives; ready to rid themselves of magical thinking and buckle up for the ride ahead.

The whisky loch is full to overflowing, as are the shelves. The question that used to be what price would you get is now whether bottles will get to shelf at all. Case in point, Uncle Nearest is now selling for as low as $19.99 in some markets, a far cry from it’s full price hey-day.

The Uncle Nearest case is still unfolding. As is Keith Batts’ case.