Your Drink Is Political: The Liquid Power Map Is Being Redrawn

What the West drinks has built empires and erased cultures. As the East rises, are we ready to embrace unfamiliar spirits—or will our resistance reveal our prejudices?

Here’s the question: When you dismiss a drink because it’s unfamiliar—too smoky, too strong, too foreign—are you exercising taste, or enforcing prejudice?

The liquid in your glass has never been just a drink. It’s a historical document, a power structure, a social contract written in alcohol and ritual. And if we’re honest about how beverages have shaped global history, we must confront an equally uncomfortable truth: what we refuse to drink reveals as much about power dynamics as what we’ve imposed on others.

As the International Wine Academy recently noted, “There is a danger of reducing wine to a mere health risk, thereby forgetting its cultural, social and human dimension.” This is the blind spot. Good drinks are the lubrication for human interaction, cultural transmission, and community identity. History is full of liquid commodities that altered destiny—and the drinks we now reject or embrace are telling us who will hold power in the 21st century.

Coffee: The Architecture of Dissent

Coffee didn’t just conquer the world; it funded it. Its journey from the highlands of Ethiopia is a lesson in the economics of cultural assimilation, but its lasting power lies in its ability to create dangerous social space.

The Kaveh Kanes of the mid-15th-century Ottoman Empire were the original disruptive technology. They were radical, accessible spaces where merchants and thinkers converged on equal footing—the original social network. Authorities repeatedly tried to ban coffee, not for the caffeine, but because these spaces were a low-cost engine for intellectual friction and dissent.

When coffee reached Europe in the 17th century, this power was amplified. London coffee houses became “penny universities”—and they weren’t just hosting the Enlightenment, they were monetising it. Lloyd’s of London started as a coffee house in 1686, where ship captains and merchants gathered to share intelligence and eventually underwrite maritime risk. Ideas and insurance policies were disseminated over the same cup, accelerating both the age of reason and the age of capitalism.

The communal ritual that coffee mandated—not just the bean’s economic value—created the modern world. Today, the Fair Trade movement isn’t just economic reform—it’s a cultural attempt to return agency to the soil and the grower, correcting colonial-era extraction one certified bag at a time.

Tea: Empire’s Thirst

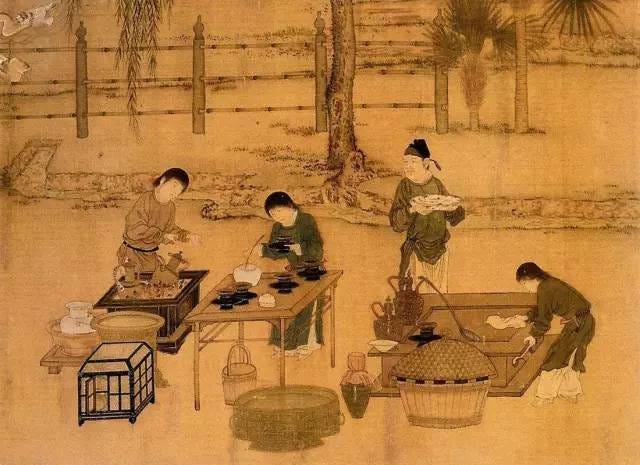

Tea’s history is a relentless accounting of global power. Originating in ancient China, it was codified into the ritual of the Tang Dynasty—representing order and purity, the antithesis of the chaos it would soon unleash.

By the 18th century, British thirst for tea wasn’t just draining the coffers—it was a fiscal crisis. At its peak, tea accounted for 10% of British government revenue through import duties alone. The resulting trade imbalance with China was so severe that the British East India Company decided the best way to pay for tea was to get China hooked on opium. One imagines the board meeting was brief.

The Opium Wars of the mid-19th century were fought to maintain Britain’s tea supply. To break China’s monopoly permanently, the British introduced commercial tea cultivation to India after discovering wild plants in Assam. A single leaf, Camellia sinensis, became the primary driver of colonial violence, narcotic coercion, and agricultural imperialism.

Yet this dark history only underscores the human dimension: the British tradition of afternoon tea became a social institution defining class and civility, while in Japan, the Chanoyu evolved into a ritual embodying harmony and respect. The same plant was infused with radically different, yet equally profound, cultural meanings across the globe. If a drink becomes a national obsession, the cost of its acquisition will define foreign policy.

Sake: The Original Liquid Diplomacy

Before we discuss China’s baijiu, we need to acknowledge Japan’s centuries-long mastery of liquid diplomacy. Sake wasn’t just refined into a technical marvel; it was weaponised as social technology.

The ritualised exchange of sake cups—with its precise hierarchy of pouring, receiving, and toasting—has governed Japanese business and political negotiations since the feudal period. The o-choko (small ceramic cup) isn’t just a vessel; it’s a power map. Who pours for whom, who drinks first, who offers the refill—these aren’t social niceties, they’re non-verbal contracts that establish hierarchy and obligation.

When Western businesses entered Japan in the late 20th century, those who dismissed sake ritual as quaint ceremony lost deals to those who understood it as binding protocol.

Fortified Wine: The Original Liquid Capital

Before tea and coffee dominated global trade, European wines were already crossing oceans—but they had a spoilage problem. The solution, developed primarily in the late 17th century, was fortification: adding grape spirits to stabilise wine for long voyages.

Sherry, Port, and Madeira became the original liquid capital. By the time fortification became widespread practice, these wines had transformed from perishable cargo into durable commodities that could survive months at sea. Madeira, in particular, became essential to the Age of Exploration—the island was a standard provisioning stop for ships heading to the New World and East Indies, and local vintners discovered that adding neutral grape spirits prevented spoilage.

This durability made fortified wines valuable beyond mere refreshment. They provided a consistent, safe alternative to water aboard ships where fresh supplies spoiled quickly. Spanish and Portuguese colonial expansion was lubricated by these wines—they were provisions, trade goods, and cultural markers rolled into one cask.

Stability, in the form of fortification, became a commercial prerequisite for maritime trade. Wherever the European flag was planted, the wine glass followed, leading to the imposition of European culture and trade priorities. The message was clear: our drinks, our rules, our world.

The Marlborough Disruption

The role of a nation in the liquid economy isn’t always defined by imperial reach. Sometimes, it’s defined by a single, high-impact sensory disruption that arrives at precisely the right cultural moment.

New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc didn’t just find a niche; it detonated the entire category. But why did it work? Through the late 1970s and 1980s, French Sancerre had established itself as the benchmark for Sauvignon Blanc—elegant, mineral-driven, food-friendly wines that graced restaurant lists globally. The style was refined, restrained, sophisticated. All the adjectives that signal “you need to understand this to appreciate it.”

Then Marlborough Savvy B arrived. Rescued cuttings were planted by Montana in 1973 with the first commercial vintage in 1979 (followed by Cloudy Bay’s launch in 1985), introduced passionfruit, gooseberry, and cut grass so pronounced it felt like olfactory assault. This wasn’t subtle. This wasn’t polite. The intensity was the point. The global market, it turned out, was ready for something that didn’t require insider knowledge to enjoy—and New Zealand provided it with confidence.

This act of liquid branding demonstrated that a small country could, through distinct flavour and timing, dictate global drinking trends and reposition itself from a peripheral primary producer to a premium taste-maker. The exchange here wasn’t about colonial reach, but the power of sensory shock and cultural confidence. If a new region can deliver a product with an unmistakable, disruptive flavour at the moment the market craves disruption, it commands cultural attention, bypassing decades of tradition.

Mezcal: The Defiance of Scale

In contrast to the globalising sweep of wine, Mezcal is a spirit of radical grounding. It is the liquid signature of Mexico, inseparable from its micro-climates, its distinct agave species, and its ancient production rituals dating back hundreds of years.

Mezcal’s allure lies in its defiance of industrial scale. The slow-roasting of the agave heart in conical earth ovens is a liturgical act—a temporal commitment that rejects the efficiency metrics of globalized spirits. The smoke, the earth, the specific hands that harvest and distill—these aren’t marketing romance, they’re the irreducible conditions of the spirit’s existence.

The current global fascination has brought economic opportunity but also an existential threat: the rush for profit risks destroying its human and ecological foundations. The challenge is whether the spirit can survive its own cultural success without severing the thread that connects the drink, the distiller, and the community. When we fetishise mezcal in high-end cocktail bars, are we honouring its tradition or beginning the same extractive process that destroyed pulque?

Liquid Stigma: The Eradication of Local Culture

The rejection of a drink is often the rejection of a people. This pattern—the powerful rejecting the liquid of the marginalised—is a recurring feature of modern history.

In 20th-century Mexico, the cultural war against the ancient agave beverage pulque provides the starkest example. Despite being a nutritional and cultural staple for millennia, pulque was stigmatised. Industrial beer companies, often backed by foreign capital, launched campaigns that framed pulque as dirty, low-class, and dangerous.

The campaign worked with devastating efficiency. Consumption dropped by over 90% in the 20th century. This wasn’t market competition—it was near-eradication through weaponised marketing and political pressure. European-style lagers became modern and aspirational; pulque became backward and shameful. The message was explicit: to be modern, to be respectable, one must drink like Europeans.

This is how global economic interests weaponise taste to dismantle local identity. When a multinational corporation can make an entire population ashamed of their ancestral drink, we’re witnessing cultural violence disguised as consumer choice.

The Shifting Liquid Order: East vs. West

If history’s liquid companions defined the British Empire and the European Enlightenment, which libations are shaping the geopolitical landscape as the global centre of economic gravity shifts East?

The Western Response: Cocktails as Syntax

The cocktail is the West’s current liquid cultural expression, and it’s revealing. It’s not about a single commodity; it’s a syntax of spirits, a fluid recombination of global ingredients. The rise of the artisanal cocktail bar reflects the Western model of late-stage globalisation: taking parts from everywhere, creating a new branded narrative, and often fetishising the global sources it blends.

This is high-art social performance, but it’s also potentially symptomatic of cultural decline. When your liquid identity is defined by recombination rather than singular tradition, what does that suggest about cultural confidence? The cocktail is magnificent, but it’s also borrowed clothes—we’re making amaro in Brooklyn, vermouth in Hawkes Bay, single malt in Tasmania. It’s the Sauvignon vs. Sancerre playbook: adapt and sell. But unlike New Zealand’s disruption, we’re not creating new categories—we’re recreating old ones with ‘same-same but different’ marketing.

There’s nothing wrong with this, but let’s not pretend it’s the same as having a drink that’s been yours for centuries, inseparable from your soil and your identity. The cocktail is cosmopolitan fluid; it’s not rooted earth.

The Eastern Ascendancy: Baijiu and Soju

The real disruption is that the West is no longer setting the terms. For centuries, Asian spirits like China’s baijiu and Korea’s soju were dismissed as regional curiosities, despite being consumed in volumes that dwarf all other spirits combined. That dismissal is becoming costly.

As China assumes greater global economic power, baijiu has become the test foreign businesspeople cannot avoid. It is the medium through which serious business relationships are established in China. Business deals are routinely won or lost over a single toast. The ganbei toast system isn’t diplomatic theatre; it’s how hierarchy gets established, respect gets demonstrated, and trust (guanxi) gets built—not just between companies, but in the informal networks where real decisions happen.

Mistakes in protocol—such as holding one’s glass higher than the senior host during a toast—are not mere social faux pas; they’re breakdowns in the non-verbal contract, signifying a failure to grasp the power structure you’re attempting to navigate. Yet Western resistance to learning this protocol is palpable. Business executives who’ve spent years mastering the nuances of Bordeaux classifications or Scotch regional styles suddenly claim they ‘don’t drink strong spirits’ when baijiu appears. The intellectual curiosity they apply to their own national drink disappears, replaced by polite evasions and barely concealed distaste. Haven’t you seen it?

By now, the double standard should be clear. Watch what happens when baijiu appears at an international spirits competition. Judges who write 200-word tasting notes on the “terroir-driven salinity” of a single farm malt will dismiss baijiu as “challenging” or “an acquired taste”—code for “I don’t understand it, therefore it has no merit.” At industry events, Western buyers lean in with curiosity for the latest Scottish distillery using experimental cask finishes, but lean back when offered China’s national spirit. This isn’t discernment—it’s cultural gatekeeping disguised as palate refinement when we ought to be leaning into the lexicon.

This isn’t invited cultural exchange; it’s required cultural competence. And here’s the difference from historical Western liquid imperialism: China isn’t asking the world to drink baijiu out of fashion or taste—it’s requiring it as the price of doing business. The West imposed its drinks through colonial force; China through economic necessity.

Korea, meanwhile, is proving that cultural seduction works faster than economic coercion. Soju’s entry into Western markets didn’t require business dinners or trade agreements—it required Netflix. Fuelled by the global rise of K-Pop and K-Dramas, soju arrived not as a requirement but as an aspiration. North American imports of Korean alcoholic beverages, including soju, increased by 18% in 2023 alone—a growth rate that trade negotiations take years to achieve.

The mechanism is entirely different from baijiu’s path. Young Western consumers order soju bombs in bars not because they need to close a deal, but because Korean culture has become genuinely cool. The two-handed pour, the turned-away sip when drinking in front of elders—these rituals are learned voluntarily, even enthusiastically, by people who’ve never set foot in Korea. They’re absorbed through screens, adopted as part of a broader cultural package that includes K-beauty, K-fashion, and K-food. This is soft power at its most effective: the target audience doesn’t realise it’s being influenced because the influence feels like personal choice.

These represent two fundamentally different models of liquid power, and the West is losing on both fronts. China’s baijiu operates through economic leverage—learn the protocol or lose access to the world’s second-largest economy. Korea’s soju operates through cultural magnetism—young people choose it because Korean culture itself has become aspirational. The West can’t compete economically with China’s requirements, and it can’t manufacture the kind of organic cultural cool that makes an entire generation want to learn how to properly pour soju.

What both paths share is this: they’re no longer asking for Western approval. Baijiu doesn’t care if you find it challenging. Soju doesn’t need validation from spirits competitions. The drinks that once had to prove themselves worthy of Western attention are now dictating the terms of engagement. The question is whether the West will adapt with genuine curiosity, or continue to mistake its declining influence for discerning taste.

Embracing cultural intimacy

Beyond the macro-shifts of empire and geopolitics, the truest power of liquid is in its ability to enforce intimacy and identity. These aren’t just drinks; they’re gatekeepers.

In Scottish culture, the sharing of the whisky quaich—a shallow, two-handled drinking bowl—demands physical proximity and mutual trust, which is why it’s so often seen at weddings. You cannot drink from a quaich without bringing the other person into your intimate space. It’s a loyalty test disguised as hospitality.

In many Pacific Island cultures, kava—a non-alcoholic drink made from ground root—is the expression of community and hierarchy. The ceremony is elaborate, the flavor is challenging (muddy, numbing, vaguely medicinal), and the ritual is essential for lubricating discourse necessary to peace and governance. To refuse kava when offered is to refuse community itself.

Here’s where Western hypocrisy becomes visible: we romanticise the quaich and write poetic tasting notes about peat smoke, but we dismiss kava as “acquired taste” or baijiu as “too challenging.” We celebrate our own ritualised drinks as cultural sophistication while treating others’ as obstacles to overcome. The whisky enthusiast who can discourse on phenol parts-per-million in Laphroaig might physically recoils from kava’s muddy, numbing mouthfeel. The sommelier who champions “challenging” natural wines won’t give baijiu a second sip. The bartender who fetishises mezcal’s smoke dismisses soju as “too simple.”

The pattern is always the same: Western drinks are “complex” or “an acquired taste worth developing”; Eastern drinks are “too challenging” or “not for me.”

All drinking cultures enforce their rules. The question is: which enforcements do we celebrate as tradition, and which do we resist as imposition? The answer reveals who we believe deserves cultural authority.

Climate, Change, and the Death of Tradition

If climate change is redrawing the wine map—Champagne houses buying land in England, Bordeaux varieties migrating to Canada, traditional regions becoming unviable—then clinging to “Old World” traditions isn’t just culturally conservative, it’s environmentally irresponsible.

The liquid geography we inherited was never permanent; it was always shaped by climate, politics, and power. Burgundy’s dominance was partly terroir, partly the Catholic Church’s medieval land consolidation. The sacred wine regions we protect with appellations and UNESCO designations were often created by the same colonial and religious forces that destroyed other drinking cultures.

If we’re willing to accept that wine regions must adapt to survive climate change, why are we resistant to cultural adaptation? If we can celebrate Tasmanian Pinot Noir despite Tasmania having no historical claim to the variety, why do we balk at Mongolian arkhi (distilled fermented milk) or Ethiopian tej (honey wine)? The resistance isn’t about quality—it’s about whose traditions we’ve been taught to value.

The Question on the Table

The liquid on the table is never just a drink; it’s part of the cultural negotiation, dictating the human dimension of future power dynamics.

When we reject a drink’s origin story, its production, or its ritual, we’re making a political statement about whose culture deserves our attention. When we refuse to learn the baijiu toast because it feels like performative submission, but we master the Scotch whisky regions because that feels like connoisseurship, we’re revealing our prejudices.

The West spent centuries using its drinks as tools of cultural imperialism—imposing wine, spirits, and beer as markers of civilisation and modernity. We stigmatised and eradicated local drinking cultures from Mexico to the Pacific Islands. We used alcohol as both weapon and reward in colonial expansion.

Now the power dynamic is shifting. Eastern drinks are demanding recognition not as exotic curiosities, but as equals—or in some cases, as the new dominant paradigm. The question isn’t whether we enjoy baijiu or soju or tej. The question is: are we willing to extend the same cultural respect to unfamiliar drinks that we demand for our own?

Because if we remain resistant to unfamiliar methods—like arkhi, the earthy and laborious mezcal process, or the challenging flavour of kava—what does that suggest about our cultural flexibility? When we dismiss an entire category of drinks because they don’t conform to our palate, are we simply being discerning, or are we, in effect, drinking racist?

What we drink, and more importantly, how we approach unfamiliar drinks, remains the clearest indicator of who holds political power and who we’re willing to share a sacred moment with.

The glass in your hand is a mirror. What does yours reflect?

A Note to the Industry

We pride ourselves on curiosity, education, and expanding palates. We host masterclasses on terroir, cask influence, and botanical selection. We ask consumers to lean in, to learn, to appreciate complexity. We celebrate the journey from novice to connoisseur.

Yet when confronted with unfamiliar spirits from unfamiliar cultures, we often fail to take our own advice.

When I host a spirits tasting, I only ask that my guests learn enough to appreciate the liquid. I never demand they like it. Appreciation and enjoyment are different things—one requires openness and understanding, the other is simply preference. The industry could benefit from applying this same principle to ourselves.

If we’re going to claim global expertise, we need global curiosity. That means approaching baijiu with the same intellectual rigour we bring to bourbon. It means learning kava protocols with the same attention we give to Champagne service. It means recognising that “not for me” and “not worth understanding” are vastly different positions.

The drinks world is being redrawn. The question is whether we’re going to participate in that redrawing with genuine openness, or whether we’ll cling to the familiar and call it discernment. Because the rest of the world is watching, and our resistance is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish from prejudice.

Category education isn’t just for consumers—it’s for us. Greater understanding doesn’t require affection, but it does require effort. And if we’re not willing to make that effort for the spirits that are reshaping global drinking culture, we should at least be honest about why.